Layered Upon, Over Time

Reprinted from A Series of Human Decisions, Decode Books, 2010

Layered Upon, Over Time

An interview with Bill Jacobson

by Ian Berry

Bill Jacobson’s recent photographic series is a quiet revolution. Its quietness is familiar in his work. The care and concentration embedded in each photograph holds us still and focused on his images. The revolution is the outcome of taking a language he had established over many years and dramatically altering its visual effect. This ambitious and expansive new project seems wholly unlike the pale, blurry portraits and landscapes Jacobson is known for making. In those works, details were set aside in favor of the symbolic power of the anonymous body, or the anonymous place. These new images reveal spaces saturated with descriptive detail. In place of figures we see a variety of architectures, but the people are more present than ever.

The series offers a calm and focused look at our surroundings, and is loaded with catalysts for memory and thought. As much as individuals were chosen to pose for Jacobson’s camera in the past, human presence now seeps in through every corner of these not-so-empty scenes. The works meticulously frame sections of weathered building fronts, corners of art deco interiors, art studios crowded with discarded materials, analysts’ offices, curtained windows, and lonely objects patiently waiting for their moment in the sun–potent details that point back to us and offer openings for questions such as: What are those objects that we continue to carry with us from place to place? What are those colors that are sure to fill us with a rush of knowing emotion? What is behind those closed blinds? What happened there, what is happening there, what will happen?

Ian Berry: How does this new series represent a change or a shift from the out of focus work you are most known for?

Bill Jacobson: First I should talk about what it meant for me to shoot out of focus, which I did from 1989 until 2002. During that time, I completed a number of series, which can also be called blurry, defocused, or perhaps diffused. I have never known what to call it, as it’s just how I’ve viewed the world. They’re intended as a metaphor for an inner state or an interior way of being. The pictures denied representations of physicality in part because there was no detail. Whether I was working in black and white or color, it reduced the images down to areas of tone, color, or forms adjacent to each other within the frame. These qualities referred to memories, dreams, and how the mind usually retains only fragments of information.

IB: What influenced this way of thinking?

BJ: I spent a lot of the 1980s collecting early twentieth-century anonymous snapshots from flea markets. They would immediately bring to mind that the subjects were no longer alive, or were decades older than when the images were made. The figures in them were often blurred or obscured, and this became a parallel for the passage of time, illness, or death. I often think of Roland Barthes writing in Camera Lucida that every photograph is of a dead moment.

IB: By shifting your work between in and out of focus, you lose and gain different things. When looking at your new in focus pictures, fragments of possible narratives jump out and make the stories they contain seem real. Do you imagine how viewers take in these works? Do you like viewers to look at them in a certain way?

BJ: I’ve learned over the years that artists make the work, and then viewers come away with whatever they choose, their own interpretation. I am open to different reactions. When I was doing the out of focus portraits in the 1990s, I recall having two studio visits on the same day. The first was from a dealer who could only talk about how handsome the men were in the photographs, and the second visit was from a doctor who said that they only reminded her of her patients who were dying of AIDS. I think they were both right, as my work usually combines elements of beauty and melancholy, whether they are in or out of focus.

IB: I think this series offers many ways in for viewers. How did you decide on the title, A Series of Human Decisions?

BJ: The title refers to the idea that we live in a highly constructed world. This was the lesson I learned once I started shooting in focus in 2004. The world is just that, a series of human decisions, one layered upon another over time. Each human action is the result of free will, and there is a spiritual dimension to this freedom. When I go to a flea market I really marvel at the tens of thousands of human creations on that acre of blacktop. That for me is an extraordinary and very beautiful thing. The experience of looking at products in a department store is not that different from looking at a much-loved painting. If you allow yourself to remove certain cultural hierarchies, both speak directly to the very human act of making.

IB: So it’s less about the specific places, or people that put this pile here, or arranged this furniture, but rather about the notion that someone did that?

BJ: Very much so. In the same way that the identities of the people or the locations of the landscapes in my earlier out of focus work were not significant. The new work is really about the idea that we’re always surrounded by other people’s creations and this becomes our visual world. We move constantly from one fabricated arena to another.

IB: When did you first start noticing these scenes?

BJ: I’ve always loved looking. I still remember being five years old and staring out the window for the longest time. And it’s clearly this fascination that led me to pick up photography, combined with feeling alienated as a teenager. I probably used the act of looking, and recording, to create a connection with the world around me, to try to figure it all out. The camera was a license to travel both physically and mentally. Over time, it brought me many places and erased many of my fears.

IB: Is this the first time you’ve exhibited an in focus project?

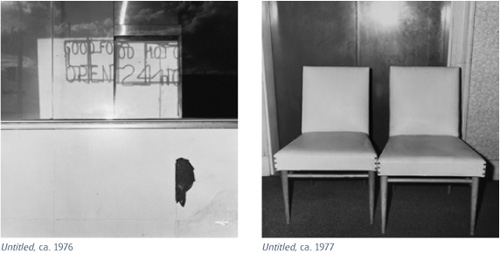

BJ: Recently I’ve been going back to my work from the 1970s when I was an undergraduate and in my first year of graduate school. It was literally the last time I had made photographs for myself in a crisp, in focus way. Like a lot students at that time, I was quite influenced by Diane Arbus as well as Lee Friedlander and Gary Winogrand. I first discovered jazz in those years, as well as Buddhism, and spent ten years meditating daily. The combination really opened my eyes, and I started seeing with incredible clarity. The individual notes I would hear listening to Mingus, for example, felt so similar to each articulated visual moment.

IB: Were there teachers that influenced you during those years?

BJ: I had some great teachers, especially Ray Metzker when he taught for a semester at Rhode Island School of Design, and then Ellen Brooks and Larry Sultan at San Francisco Art Institute.

IB: Has anything changed in your life more recently that has influenced this new work?

BJ: It had a lot to do with moving out of my old loft in the East village. After twenty years of living in one place, I had collected so many objects, pieces of furniture, photographs, found snapshots, artwork by friends, postcards, and magazines. The loft was large and when it came time to condense everything and pack it down, I spent several months looking closely at the thousands of things I’d amassed. Dismantling this one space made me realize how put together my immediate environment had been and I began to notice making, collecting, and constructing in the world at large. I started looking at other spaces and objects and shooting as many as I could.

IB: What types of spaces did you focus on?

BJ: A lot of these new pictures are of artists’ studios because they suggest the process of creating. Some are of analysts’ offices, partly because I think we construct our ideas and our personalities in those rooms, and I like that usually they are put together in a very considered way. There are also plaster casts of Renaissance sculpture and interiors of an important Art Deco house in upstate New York. There are objects in thrift stores. There are pictures of middle class Dutch housing I did for a commission from the Noorderlicht Photogallery. I went to Barcelona specifically to photograph the unfinished interior of Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia. Some of the pictures are of city walls that have been painted and repainted for utilitarian purposes. All of them are constructed environments. I could keep making pictures like this for many years.

IB: The notion of photographing everything–an encyclopedic archive project–has a tradition in photography from August Sander’s Portraits of German People to Gerhard Richter’s Atlas, even Zoe Leonard’s Analogue. Do you situate this project in that history?

BJ: It’s a much looser kind of archive. I think it suggests the world, but doesn’t attempt to archive a particular aspect of the world.

IB: Is there a connection to the commercial photography you’ve done over the years?

BJ: Between moving to New York in 1982, and the mid-1990s, I took pictures for many galleries, artists, and museums. During that time, I photographed thousands of objects, paintings, sculptures, and installations. Doing the commercial work so intensely for so many years helped me break down the categories of high and low, and question the difference between art and object, and between architecture and utilitarian construction. These new pictures suggest this kind of equivalence.

IB: When you look at your work for hire, photographs of other people’s artwork, do you see your artistic self there? There are a lot of constraints; you are not able to make all the decisions.

BJ: The one constraint, of course, is that the commercial work needed to be in focus. Otherwise, whether I’m photographing somebody else’s work or making a picture for myself, it actually summons the same cells of my body, the same set of eyes. I’m painfully conscious of lighting, composition, editing, what’s included, what’s excluded, how the film is processed, how eventually that image is printed and subsequently reproduced. The process is much the same, whether it is in focus or out of focus, whether it’s of an Ellsworth Kelly painting, or a piece of paper in a shop window. I think it calls to mind a similar range of decision-making. They’re my decisions which lead to a picture that works, or doesn’t.

IB: Let’s talk about some of your decisions. How are you editing this body of work–what are you looking for? As you said, there is a lot of artwork on walls or artwork in studios. There are a lot of openings, windows, shades, doorways …

BJ: … rectangles.

IB: Rectangles, openings. Were you looking for those things, did that help you edit?

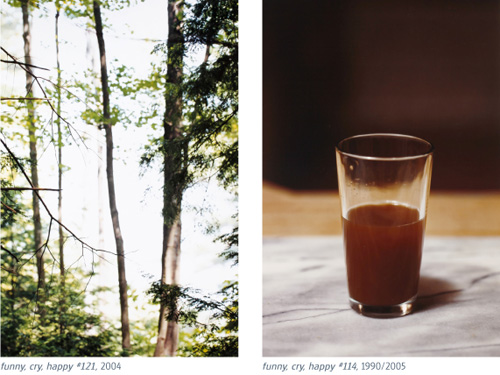

BJ: Some of the images here are drawn from a slightly earlier body of work called funny, cry, happy, which was my first in focus series in many years. I had to teach myself how to both see and shoot in focus after fifteen years of not doing it. Initially I was making images of nature, interiors, and some faces, until I realized what interested me most was humanly constructed space. I became drawn to the rectangle as something which really doesn’t exist in nature, but which also represents an archetype of our visual journey through the world. So much of what we make is consistently rectangular. You find it constantly in art and architecture, furniture and signage, and all books and photographs. But it’s not only visual … I think the rectangle exists as an emotional portal as well.

IB: How did you come up with the title, funny, cry, happy?

BJ: Oddly, it used to be the name of a smoke and magazine shop on 14th Street. It was the most wonderful urban poem I had ever seen, and it always made me think of Zoe when I saw those words on the store’s awning. The images in funny, cry, happy were cropped quite vertically, as I wanted them to reflect their connection to the body. In contrast, A Series of Human Decisions suggests the mind, and perception, and for me the prints’ square format reflects that.

IB: Speaking of rectangles and squares, there is a certain group of pictures here of windows that we can’t see through. Maybe I’m making too much poetry out of it. A window by itself is already loaded with notions of what’s inside and what’s outside, and how we see, and how we see through. Your windows are often draped. There is a mystery of what’s going on behind these windows.

BJ: A veil, or a curtain, is actually another planar surface. I’m attracted to a layering of materials in a lot of these pictures, and so a curtain in front of a window becomes one more layer. Emotionally I’d say they refer to my out of focus work, which addressed what can’t be easily seen.

IB: I keep returning to some of these narrative ideas when you say human decisions, it makes me think about things other than formal choices, other than color and line. Call those formal decisions, or conceptual decisions, but human decisions sound more emotional.

BJ: It’s true … I’m the first to admit that the decisions we make are a hybrid of both physical and emotional needs. Similarly a photograph can simply be a document of ‘what is’, or it can be about a sense of longing, or desire, or love.

IB: The work also suggests collecting and arranging, and how we manage our space.

BJ: Certainly collecting and arranging is part of the sequence. First the objects are made by one person or a group of people, then acquired by another, then possibly arranged by someone else. Then I photograph them in a particular kind of light, and then a print is made at a certain size, framed, and possibly positioned on a wall. These are all creative decisions.

IB: Finding inspiration and energy from everyday objects or seemingly mundane things is something that I often associate with poetry. From John Ashbery and his peers to younger poets who also refocus us on the everyday–these poets find great catalysts for all kinds of emotions and thoughts in those moments. You are doing that with these pictures.

BJ: It’s a good analogy. There has always been a poetic stance in my work. Whether in focus or out, it’s never been about a single narrative, but rather something beneath the surface of what’s being photographed. And while there is a story here, I agree with you that it’s fairly open-ended.

IB: This series seems to flow in and out of time zones. I was thinking about you and thinking about how this could relate to your life and your experiences. Is this some kind of place that he is attracted to because of where he grew up or a place where he visits? They don’t seem to be places of a modern, contemporary world–there are no computers, there is very little technology, they have a feeling of another time.

BJ: A few feel contemporary, mostly the artist studios, but many refer to a range of past decades. I’ve always been inspired by old photographs and their ability to transport the viewer back in time. When I was young, I was the person in my family who really liked visiting older relatives. Their houses, belongings, and ways of being all reflected an earlier time. To be in their world was like being in an old snapshot. And of course they had numerous family albums to look at, so the whole experience was a kind of time-traveling. I constantly sense the layering of time, and my photographs have often been about suggesting those layers. It’s one of the reasons I prefer New York to Los Angeles. Because it’s an older city, I find more layers to uncover here.

IB: I am still musing on the private and the guarded, and what is uncovered and covered. These photographs are quiet but they are also full of energy and very charged. Many are still, focused, and very concentrated, but never without a lot of buzzing around the edges.

BJ: I think that’s how objects are when we stop to really look at them. If we quietly observe, we see they suggest the many hands that have touched them. If we really look at a brick wall, we can feel the energy of the bricklayer. The image of the cupboard is more than that–it can channel the energy and personal histories of those who have opened and closed it multiple times. There can be fascination in the most mundane if you’re open to it. A piece of paper in a window, or a pair of roller-skates …

IB: Those are monumental skates. Where did you find them?

BJ: In a thrift store in New Hampshire.

IB: That picture freezes a moment of innocence or pleasure. Maybe that could be a connecting line between the images–the excitement and energy of being in an artist’s studio can also offer that freezing of a moment of inspiration, a moment of excitement or that spark of a first meeting.

BJ: I encountered many of the places I photographed while walking the streets with a 4×5 view camera. There are some that I searched out based on an idea, such as the therapists’ offices. Several were taken at a museum in the town where I grew up, the Slater Museum in Norwich, Connecticut. The collection today is mostly the same as it was when I was first there in the late 1960s. It’s primarily a plaster cast museum, and was both my first exposure to art and the first time I saw the nude male figure in art.

IB: Was high school the time you discovered those passions?

BJ: Not overtly, but covertly. I ended up coming out a few years later. But it was in high school that I discovered that museum and would visit it frequently. And I also found the Diane Arbus book with the twins on the cover. These two experiences completely changed me, and I began to realize the power of images. Together they started me thinking about making a commitment to photography.

IB: So is there a bit of a diary-like aspect to this new project?

BJ: If it’s a diary, it’s one that’s constantly being rewritten. The first picture in the book is of a blank piece of paper, and the last includes a clock on a museum wall in which the time is obscured by a dark shadow. Both refer to details that are missing, eventually to be filled in.

IB: In any archive or collection you cannot help but see a story about the collector and the context.

BJ: For me one of the stories here is the change that’s come about in my way of perceiving the world these past few years. There are many others as well … some are mine, some are yours, and they are all true.

Ian Berry is The Susan Rabinowitz Malloy Curator of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College.